Historic Iron

Did you know that Clifton Suspension Bridge is made of iron? The bridge's ironwork is Victorian, and requires special care.

The majority of Clifton Suspension Bridge is made of wrought iron and most of it is original, making the bridge perhaps one of Bristol’s most significant historical artefacts.

What is wrought iron?

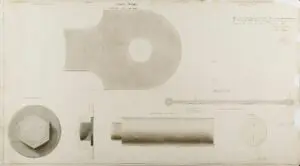

Worked or wrought iron is less brittle and more malleable than cast iron. It began to be manufactured on a larger scale in Britain from 1784 onwards using Henry Cort’s puddling process. This involved agitating molten cast or pig iron with a long pole (i.e. puddling) to remove carbon and then rolling or squashing the iron when hot to cast out excess molten slag. The iron was re-worked by being cut up, melted and re-rolled to reduce imperfections and the more times it was done so, the higher quality of the iron. This iron became known as ‘Best Iron’ and if gone through the process twice, ‘Best Best Iron’, and so on.

All the iron used for this Contract shall have been first knobbled under the hammer when taken from the Puddling Furnace and rolled into rough bars, these rough bars shall then pass through the several processes of cutting up, heating and rolling at least twice before they are delivered to the Smiths for the purpose of forging or welding.

Extract from the 1840 specification for Clifton Suspension Bridge’s ironwork (Ref. DM2121)

Wrought iron stopped being manufactured in Britain in the mid 1970s; this was because it was too time consuming and costly to produce compared to steel.

How much of the bridge’s ironwork is original?

The majority of the bridge’s ironwork is original. If parts cannot be refurbished then they are replaced with the intention of keeping the historic integrity of the structure. Because the bridge is a Grade-1 listed, all work is approved and overseen by Historic England. As some of the original iron production methods are no longer common practice, this work has to be carried out by specialist contractors. Excluding the replacement of small bolts and pins, so far the following replacements have been made:

- 2 out of 81 cross girders under the carriageway of the bridge were removed for testing in the 1950s and replaced with steel

- 1 out of 4200 wrought iron chain links was removed for testing in 1983

- 37 out of 162 cast iron parapet stanchions (joints) have been replaced since 1993 with spheroidal graphitic cast iron replicas

- 13 out of 162 hangers have been replaced, 10 of them in 2010/2011 using corrosion resistant, low alloy structural steel

- While they have been cleaned, no parts of the two original wrought iron saddles over which the chains pass over the tops of the towers have been replaced

This means that 53 out of 4607 iron parts – approximately 1.15% – of the bridge’s ironwork has been replaced. You could say that 98.85% of the bridge’s ironwork is original.

How old is the bridge’s original ironwork and where did it come from?

Strictly speaking, the bridge’s original ironwork is not found on Clifton Suspension Bridge but now forms part of the Royal Albert Bridge. In 1840 Joseph Carne and John Vivian of the Copperhouse Foundry in Hayle, Cornwall were contracted to manufacture the ironwork to Brunel’s specifications for Clifton Suspension Bridge using iron supplied by the Dowlais ironworks in South Wales. While the majority of the specified ironwork was delivered, in 1853 it was sold off to pay debts and used for another of Brunel’s projects – the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash.

However, while the ironwork was being produced for Clifton, at the same time Carne and Vivian were also producing similar iron bar chains for Brunel’s Hungerford Suspension footbridge in London.

When the footbridge was demolished in 1862 to make way for the Charing Cross railway bridge, the chains were reused at Clifton by engineer, John Hawkshaw.

At this point, two thirds of the iron chains destined to become the current Clifton Suspension Bridge were supplemented with additional ironwork manufactured by contractors Cochrane, Grove and Co Ltd. It is likely that Cochrane, Grove and Co sourced their iron from foundries in Staffordshire and the Midlands.

So, two thirds of the chains date from 1840 and are around 184 years old, while the rest of the ironwork dates from c.1862 and is around 162 years old.

Iron needs to be protected to stop it rusting; when exposed to oxygen and moisture in the air it forms iron oxides. This process is speeded up by chlorides – or salts. Even though the bridge is 75.5 metres above the high tide of the River Avon, it is classed as being located in a marine environment. This is why it is vital to keep the bridge’s paintwork in tip top condition.