One of the most distinctive features of Clifton Suspension Bridge are its hand forged wrought iron chains. The Refurbishment Works gives us an opportunity to investigate and test the strength of the chains. How are they holding up after 160 years or more of use?

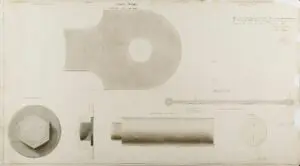

Clifton Suspension Bridge consists of two sets of three chains, one set on the north and the other on the south side of the bridge. The chains are made up of a total of 4200 wrought iron eye bar links, which range from 4.8 to 7.2 metres in length. Each chain sits above the other, with either 11 or 12 links placed adjacent to each other and bolted together – a bit like a bicycle chain.

The chains pass over saddles mounted on a series of rollers at the top of the two towers and are anchored 20 metres below ground in the underlying rocks either side of the bridge in Clifton and Leigh Woods. On each side, hanging from each of the three chains in turn are the hangers, which are equally spaced in 2.4 metre intervals along the span of the bridge.

The original chains that were specified and ordered for Clifton Suspension Bridge were never used; they were sold off in 1853 to the Cornish Railway Company and were used to build Brunel’s Royal Albert Bridge.

Two thirds of the links that make up the current structure of Clifton Suspension Bridge were re-used from the chains of Brunel’s demolished Hungerford Footbridge . The Hungerford chains had been designed and ordered at the same time as the original Clifton Suspension Bridge chains and were also manufactured by Vivian, Carne and Sandys at the Copperhouse Foundry in Hayle, Cornwall between 1840 and 1843 from Dowlais iron. Once the Hungerford Bridge was demolished, the chain links were delivered from London via the Great Western Railway to the Bristol site in 1862.

In the 1860s, engineers, Hawkshaw and Barlow adapted Brunel’s design for Clifton Suspension Bridge by adding an additional set of chains. The additional links were made using wrought iron perhaps sourced from the Round Oak works in Staffordshire and then manufactured by contractors, Cochrane Grove and Co at their Woodside foundry in Dudley between 1861 and 1862. The three chains are made up of links from both periods of manufacture, with the newer 1860s chain links tending to be predominately placed near to the tops of the towers and the middle of the bridge.

A link is removed…

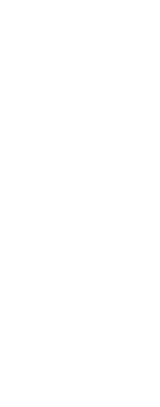

In January 1983 one link was removed for testing from the middle of the bridge on the north chain from the outer side facing the footway (link number N20). This link was permanently replaced by a mild steel link sprayed with aluminium in July of the same year. This is the only link that has been removed and replaced during the lifetime of the bridge.

Deciding to permanently remove part of the bridge was a serious decision; so, why were the tests needed? Since the early 1970s, engineers had been concerned about the fracture toughness of wrought iron as well as how well the bridge could cope with fatigue. This was in part prompted by the Point Pleasant Bridge (or Silver Bridge) collapse of 1967, which was shown to be caused by the brittle fracture of an eye bar chain link. While the Point Pleasant Bridge was made of steel – not iron – a wrought iron bridge had collapsed in 1956 in Ireland and numerous ship’s wrought iron anchors were known to have failed. To what extent were the chains of Clifton Suspension Bridge susceptible to similar weaknesses?

In 1973, engineers closed Clifton Suspension Bridge to carry out loading tests, measuring the strains on various locations of the eyeholes of the chains at critical points on the bridge. They also manufactured a full-scale model chain link and tested it. This model was made of steel because not enough wrought iron could be found. While they found that annealed steel behaved similarly to wrought iron and that results indicated that the risk of failure due to fatigue was low, the potential of a brittle crack fracture still could not be fully ascertained.

One problem was finding and understanding the specific properties of the iron used for Clifton Suspension Bridge. Old nineteenth-century wrought iron from Menai and Britannia bridges were examined and tested for fractures, but the variance was so great between the samples that no conclusions could be fully established.

The only way of finding out would be to test an original iron link sample from Clifton Suspension Bridge. A ‘newer’ link manufactured in the 1860s was carefully chosen as a) being similar to the links under most strain on other parts of the bridge, b) high in phosphorus and sulphur (deleterious to iron), and c) near the middle of the bridge and therefore safer to access.

Removing a link is no easy task – despite this being one of the shortest links at 15 ft 3” (5.33 metres), it still weighed 185.6kg. To remove it, it was slowly heated and moved using steel shims.

Once removed, extensive tests of the link enabled the engineers to finally conclude that the likelihood of failure from fatigue or from brittle crack fracture was ‘extremely unlikely’ and could be discounted.

Current tests

Over 40 years later, the current refurbishment project has offered the opportunity to undertake further investigation of the chain links and the pins that connect them. 4 pin caps were carefully removed to enable an inspection of the pins beneath, which were found to be in excellent condition.

Paint was also removed from the chain links to enable Magnetic Particle Inspection (MPI) of the wrought iron. MPI is a Non Destructive Testing (NDT) technique that enables the inspector to check for surface breaking defects in the metal (e.g. cracks and voids). No significant defects were found during the inspection.