In December 2013, we saw these tweets on Twitter:

More followed, all suggesting that our bridge would be the ideal location for this project. We were intrigued! We’d never heard of anything like this before, although we had read historic reports talking about the bridge ‘singing’ in strong winds. We had to find out more and visited the project website www.humanharp.org. Here’s what it told us:

Walking across the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, artist Di Mainstone was inspired by the cacophony of sounds that she heard – the clonking of footsteps on the walkway, the whirring of bicycles, the drone of traffic and chatter of visitors. It struck her that all of these journey sounds were resonating through the steel cables of the bridge and she wondered if she could collaborate with specialist researchers to develop an instrument that would enable pedestrians to release and play these deep hidden sounds.

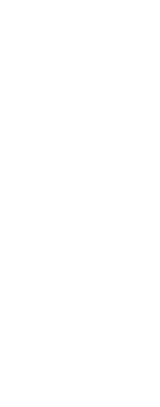

Concept sketch for the first Human Harp

When Di discovered that the 130th anniversary of the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge was imminent on 24th May 2014, she saw this as an opportunity to realise her vision of turning a bridge into a giant musical instrument and so approached Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) to fund the development of the first version of the Human Harp. Collaborating with digital start-up Anti-Alias, students from the university’s Centre for Digital Music and its Media and Arts Technology group, as well as twenty MA students from Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design, the Human Harp was made and ready for its first outing.

“On the 130th anniversary of the Brooklyn Bridge, we connected dancer and movician Hollie Miller to the Human Harp and she played the bridge. Intel’s Creators Project made a film to illustrate how our instrument worked and the project went viral…”

Di Mainstone

Human Harp > 130th Anniversary Intervention, Brooklyn Bridge from humanharp on Vimeo.

In January 2014, Di Mainstone made her first visit to the Clifton Suspension Bridge and began to sketch her ideas for the Human Harp. She also met with Pervasive Media Studio at the Watershed, who also loved the project and offered her a residency so that she could develop the ideas.

“Imagine a rich, rumbling melody drawing you towards Clifton Suspension Bridge on a misty spring morning. It is the 150th anniversary celebration of Brunel’s bridge. As Clifton’s soaring piers reveal themselves, we follow a gentle stream of bridge watchers. Traversing the bridge along the pedestrian walkway, we pass bridge players (called ‘movicians’) positioned along the bridge’s centre – which is closed to traffic. Part bridge and part instrument, the movicians take on characteristics of the bridge’s architecture and stonework.”

Clipped to suspension cables via colourful retractable strings which are tethered to their holsters – the movicians sway to and fro releasing deep droning bridge vibrations. These sounds are controlled by each player’s motion and projected through speakers positioned the length of the bridge. The rest of this tale involves you, your footsteps, chatter and vibrations, which will create the frequencies captured and played by the movicians. Surrounded by an inspiring panorama, together we will co-create a visionary bridge opera that perhaps even Brunel might have hummed along to…”

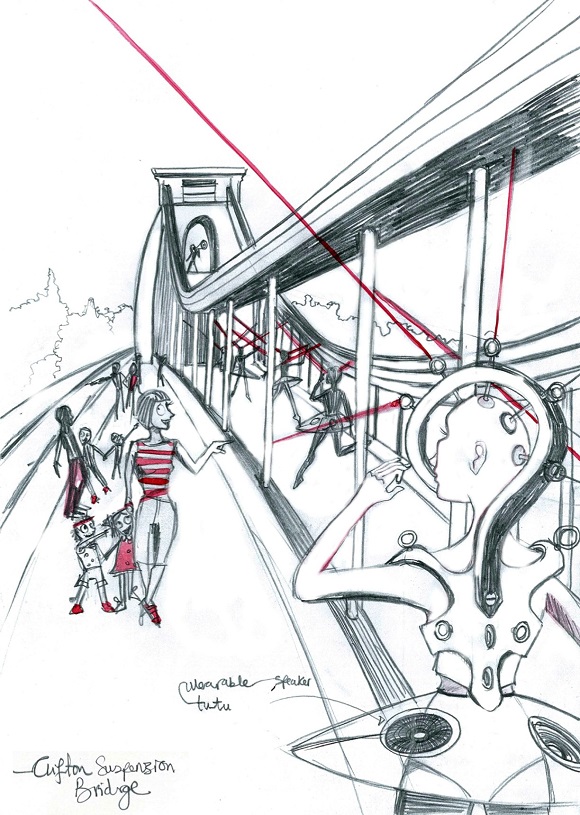

Concept sketches for Moveicians at Clifton Suspension Bridge

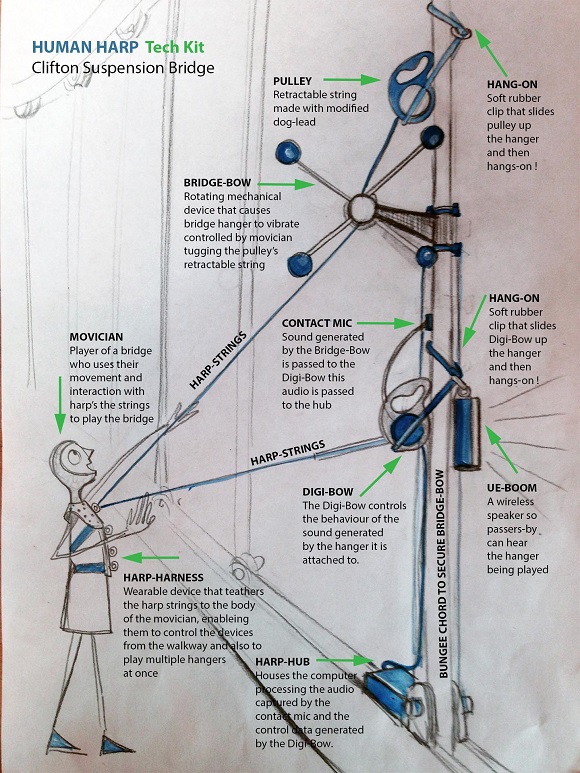

Concept Sketches for the Human Harp Kit

Di then returned with Adam Stark, a musician and coder who had previously worked with Imogen Heap, to record the vibrations running through the longest (20m) hanger on the bridge.

Di’s investigations took her to some new and exciting locations. She was invited to be an Artist in Residence for the Reverb Festival at the Roundhouse in London where her team set up a pop-up laboratory testing their new digital ‘Harpnotes’ with visitors and musicians throughout the month of August. They also had the opportunity to create two performances in the main circular space in the venue as part of the Reverb Festival line-up.

“Artist Di Mainstone and the Human Harp team were a key part of the Roundhouse’s summer events this year. We absolutely loved having the Human Harp’s pop-up laboratory on-site throughout August and saw how their innovative musical instrument really engaged and inspired our visitors young and old. The Human Harp performances in the main space were both beautiful and engaging – we hope these may be able to happen again in the future…”

Rachel Nelken, Senior Producer at the Roundhouse

Next, Di went to Omaha on a residency at the Bemis Centre for Contemporary Arts where she worked with musicians, dancers, architects and a maker of musical instruments to explore ways of bowing a plucking the suspension cables of Bob Kerrey Suspension Bridge, a S-shaped pedestrian bridge.

“During the Roundhouse Residency, I realised that we were only at the beginning of our journey. We had collectively made a portable, playful sonic device that would allow its players to sculpt sound in creative ways. However there was a huge gap in our knowledge surrounding the physics of the bridge and the way in which sound would travel through suspension roads and cables. The beauty of the Omaha residency was that every day was spent outside on the bridge meeting specialists who understood physics and sound. The result being the development of our mechanical bridge bow…”

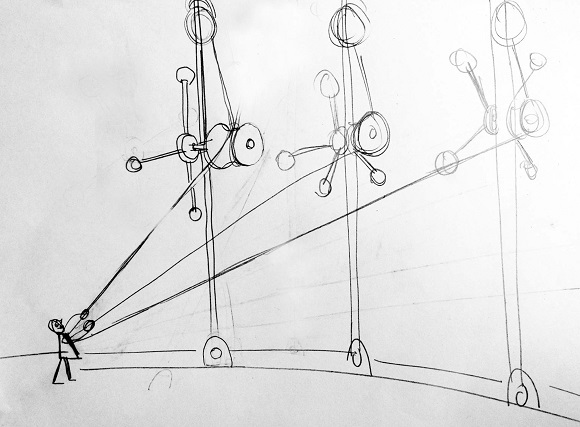

Di came back from Omaha bursting with ideas, envisaging a completely new system for playing Clifton Suspension Bridge that would be a combination of a mechancial player, controlled from the walkway by a long cable which could spin a rotating device to pluck the hanger, and a digital interface which would capture the resulting sounds and enable the player (or ‘Movician’) to manipulate the sounds produced (eg.: reverb, pitch or volume) via rectractable cord. Di presented a sketch of the interface to the engineers at Arup’s Bristol Office and began working with engineer Roland Trim to develop the first prototypes. The first prototype was tested on the bridge in December 2014 and whilst it managed to vibrate the hangers some problems arose as the movician needed to remain in the same position to prevent the harp string from jumping off the pully. The team then decided to design a spinning ‘bridge bow’ that would allow the movician to move along the bridge’s walkway and play multiple hangers at once.

An initial sketch

Testing the idea

Developing the idea

The final system

Following the research of Alessia Milo of Queen Mary University of London, Di and the team began exploring the concept of the ‘Clifton Scale’. Alissia noticed parallels between Clifton Suspension Bridge and a harp or piano in that the rods or hangers on the bridge are halved in height every 12 hangers. This meant that the hangers of the bridge could naturally create a 12 tone octave.

A recording of the “donging” of 30 suspension rods on Clifton Suspension Bridge. Each cable or hanger is “donged” with a rubber ball starting with the longest (20 Meters) by the tower and moving to the shortest in the middle (about 50cm).

Di is currently working with Jesse D. Lawrence (film maker), Early Day Film Productions, Pervasive Media Studio, Arup, Seb Madgwick (engineer), David Blair-Ross (Industrial Designer), Becky Stuart of Anti Alias Labs and Adam Stark (musician/coder) to further develop the project. Hear Di and Jesse talking about the project to Colin Moody on BCFM, broadcast 26th February 2015.

Work in progress – March 2015

The digi-bow connects to the hangers via the blue ‘hang-on’, and fastens with a carabiner.

Di developed a new harness especially for the Bristol performance, inspired by the cream and grey colours of the bridge.

London based industrial designer David Blair Ross designed and 3D printed the new digi-dome which will house the technology in the digi-bow.

In May 2015, Di launched the #PlayTheBridge film Trailer at This Happened, Bristol.

About Di Mainstone

The New York Times has listed Di Mainstone as one of the top six ‘New Generation Visionaries’ in the International Digital Arts Scene. As artist in residence at QMUL, Di collaborates with researchers from the Centre for Digital Music and Media Arts and Technology group. Di’s work at QMUL involves developing new musical interfaces that are “body-centric”, transforming physical movement into sound via digital technology. Di has created a pioneering method of building sonic interfaces on the body of dancers, coined ‘body-centric’ design. She has ten years of experience at the forefront of interactive digital arts, collaborating with organisations such as Banff New Media Institute, XS Labs in Montreal, V2 in Rotterdam, Media Lab in Cambridge Massachusetts, Eyebeam in New York and QMUL. Di has showcased her sonic devices internationally at venues including The V&A, The Barbican, The Swedish National Touring Theatre, The National Portrait Gallery, Berkley Art Museum, Eyebeam Centre for Art and Technology, Boston Science Museum and Dublin Science Gallery. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, the New Scientist, the Observer, Dezeen, Huffington Post and many more…