Joseph Rogers, who recently launched his first Amberley title Britain’s Greatest Bridges at the Clifton Suspension Bridge Visitor Centre, looks at the connection between the engineering icon Isambard K. Brunel and his current place of work at the West Somerset Railway.

1856 saw Brunel at the centre of a number of projects throughout southern England. At Saltash, construction of the Royal Albert Bridge was under way, linking Cornwall with the rest of the nation by rail. The Clifton Suspension Bridge near Bristol was also partially complete but had somewhat stalled for a number of reasons and the SS Great Eastern was also on its way to being completed ready for its launch in 1858.

This year also saw his advice being offered to a collective of landowners in West Somerset as they sought to promote the concept of a West Somerset Railway, linking the historic harbour town of Watchet with the rest of the region and beyond. The area was keen to transport stone and iron from the numerous quarries and through a railway already existed in the form of the West Somerset Mineral Line, a connection with the Bristol and Exeter Railway was thought necessary to expand the reach of the area’s resources. Previous decades had seen the idea of a Watchet to Bridport link put forward, meaning freight could bypass the Cornish peninsula by rail rather than go round by sea.

Watchet Harbour

The question lay over the proposed route and whether that route should connect with the Mineral Line or become a standalone, linked to the mainline. Though Watchet was the key in procuring interest from an industrial point of view, the ability to link passengers to Minehead and Porlock was also considered.

The mainline connection was keenly pushed but with uncertainty over the point of junction. Those in Taunton believed it a certainty that a connection there would offer greater benefits, such that when Bridgwater was pointed out as an alternative, it came as something of a surprise. The latter point was supposedly favoured by Brunel, who sought to further his ambitions for challenging engineering feats and complex solutions by constructing a tunnel beneath the Quantock Hills and out north to Bridgwater.

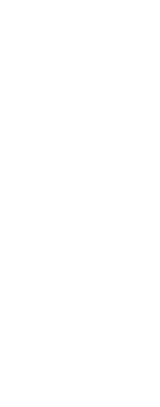

Illustration from “An exploration of Exmoor and the hill country of West Somerset with notes on its archæology … With map and illustrations” by John Lloyd Warden Page

Costs saw that idea fade, however, and instead it was decided that the route would come off the mainline at Norton Fitzwarren, before heading northwest along the valley occupied by Stogumber, and out to Watchet along the Donniford Brook (now often referred to as Doniford Stream). A meeting on 1st August 1856 saw the arguments laid against one another before a vote resulted in the Taunton route succeeding over Bridgwater. While the subject of Minehead was raised quite considerably, there was no intention at this stage of constructing the line that far west.

Brunel had appointed his assistant James Burke to assist with surveying the area and gathering data to determine the railway’s route. Brunel did visit Watchet himself during this year but was otherwise preoccupied with other projects bearing his name. Eventually he would end up being embroiled in the plans to modify the harbour itself.

The West Somerset Railway eventually opened in 1862, three years after Brunel’s death. By 1874, the growing tourist trade prompted the extension to Minehead, as originally discussed, via Washford and Dunster beach. Services ran until 1971, when it was closed via the Beeching Axe, despite the trade offered to the area by the growing Butlin’s holiday resort. After five years of closure, the line was reopened as a heritage line.

Today Brunel’s impact on the line exists not only through its existence as England’s longest heritage railway for tourists and enthusiasts, but also in the attraction’s mascot – Brunel K. Beagle. 2019 sees the railway celebrate 40 years of the line being reopened to Bishops Lydeard and although it no longer runs through to Taunton in a regular capacity, it still accommodates charter trains, guest locomotives and, more recently, Royal rail users, via the connection to the mainline at Norton Fitzwarren.

Further reading: The Minehead Branch (1848 – 1971) by Ian Coleby.