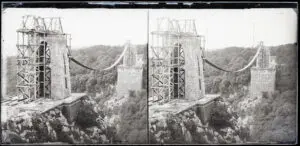

This animation shows the bridge during the final stages of its construction in 1863. Illustrated is one of the wooden and iron wire falsework bridges made to support the construction of the wrought iron linked chains across the bridge.

Alastair Carr describes the process of creating this animation

As part of my degree’s final year for computer animation at NCCA, Bournemouth University, one of the last units we were given was for Cultural Heritage. The task was open ended, and we could make pretty much whatever we wanted. Growing up around Bristol, I soon realised that Bristol’s iconic bridge would be a great choice for my project – I would make a 3D model of it during construction. Thanks to the wealth of archived stereoscopic images taken during its construction, I had no shortage of reference material to model with.

I started by collating various interesting images from the archives into a timeline, mainly so I could find a good period of its construction to work with, and so that I could get a better idea of the entire process. I ended up settling on a stereoscopic image from 1863, where the chains are being prepared to be placed upon a wooden falsework bridge held up by tensioned iron wires. The high-quality version of this image made it much easier to see the finer details. The fact it was a stereoscopic photograph, an old technique somewhat similar to modern-day VR by taking two photos an eye-width apart, was also extremely helpful.

Given it’s an old photographic print produced using Victorian technology, it’s no surprise that the image has imperfections. I’m not sure whether these would be dirt during on the camera lens or deterioration of the photographic print, but the image is covered in small dots, which can make some areas a little harder to see. The two different images also have different levels of focus, which makes one of the images a little blurry – however, since it’s a stereoscopic photograph, it wasn’t too much of a problem as I could simply double check with the other image!

I’m something of a perfectionist – I like to make things perfectly to size when I can, and this project was no different. However, finding accurate measurements of the bridge turned out to be trickier than I had thought.

My first attempt started with tracing photos of the bridge I took in person, and turning it into a 3D model, however this wasn’t particularly reliable as the perspective of a pedestrian distorts the images too much.

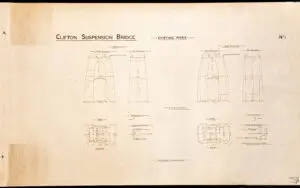

Having failed that, I searched further for diagrams that would use concrete numbers. Fortunately, a fairly detailed diagram of the towers did exist in the archives, far better than any I had found so far. This was a copy tracing made by engineer, Frederic Gleadow in 1903 that was based on drawings made by the construction company for the second phase of building, the diagram had a lot of precise measurements that were extremely helpful. Since the towers were already constructed by this point, I believe these diagrams were specifically for guiding where to place the scaffolding. Unfortunately, this means some of the less important measurements were excluded, but I could guess or calculate them to be close enough.

I was initially going to model and texture the bridge in a fairly realistic style, however I soon found out that would be impractical, especially with the remaining time I had. I found that I couldn’t simply paste real images onto the 3D model – the perspective was still a problem for one, but the bridge also looks significantly different to how it did, the bricks more weathered, speed limit signs added as well as an annoying barrier and cars that kept blocking my photos! Instead, I opted for a more stylised approach, only slowly the outlines of key details, drawing the pattern for the masonry myself. With a little shader adjustment in Maya (the software I used for this), most of the outlines drew themselves too!

Overall, I’m pretty proud of how it came out – there’s still some details that I’m not happy with, but there are always mistakes in creative projects. I’m really glad to have worked on this, and I really want to thank Hannah Little (Archivist) for the help she gave for this project.

By Alastair Carr